10. NumPy#

“Let’s be clear: the work of science has nothing whatever to do with consensus. Consensus is the business of politics. Science, on the contrary, requires only one investigator who happens to be right, which means that he or she has results that are verifiable by reference to the real world. In science consensus is irrelevant. What is relevant is reproducible results.” – Michael Crichton

In addition to what’s in Anaconda, this lecture will need the following libraries:

!pip install quantecon

10.1. Overview#

NumPy is a first-rate library for numerical programming

Widely used in academia, finance and industry.

Mature, fast, stable and under continuous development.

We have already seen some code involving NumPy in the preceding lectures.

In this lecture, we will start a more systematic discussion of

NumPy arrays and

the fundamental array processing operations provided by NumPy.

(For an alternative reference, see the official NumPy documentation.)

We will use the following imports.

import numpy as np

import random

import quantecon as qe

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d.axes3d import Axes3D

from matplotlib import cm

10.2. NumPy Arrays#

The essential problem that NumPy solves is fast array processing.

The most important structure that NumPy defines is an array data type, formally called a numpy.ndarray.

NumPy arrays power a very large proportion of the scientific Python ecosystem.

10.2.1. Basics#

To create a NumPy array containing only zeros we use np.zeros

a = np.zeros(3)

a

array([0., 0., 0.])

type(a)

numpy.ndarray

NumPy arrays are somewhat like native Python lists, except that

Data must be homogeneous (all elements of the same type).

These types must be one of the data types (

dtypes) provided by NumPy.

The most important of these dtypes are:

float64: 64 bit floating-point number

int64: 64 bit integer

bool: 8 bit True or False

There are also dtypes to represent complex numbers, unsigned integers, etc.

On modern machines, the default dtype for arrays is float64

a = np.zeros(3)

type(a[0])

numpy.float64

If we want to use integers we can specify as follows:

a = np.zeros(3, dtype=int)

type(a[0])

numpy.int64

10.2.2. Shape and Dimension#

Consider the following assignment

z = np.zeros(10)

Here z is a flat array — neither row nor column vector.

z.shape

(10,)

Here the shape tuple has only one element, which is the length of the array (tuples with one element end with a comma).

To give it an additional dimension, we can change the shape attribute

z.shape = (10, 1) # Convert flat array to column vector (two-dimensional)

z

array([[0.],

[0.],

[0.],

[0.],

[0.],

[0.],

[0.],

[0.],

[0.],

[0.]])

z = np.zeros(4) # Flat array

z.shape = (2, 2) # Two-dimensional array

z

array([[0., 0.],

[0., 0.]])

In the last case, to make the 2x2 array, we could also pass a tuple to the zeros() function, as

in z = np.zeros((2, 2)).

10.2.3. Creating Arrays#

As we’ve seen, the np.zeros function creates an array of zeros.

You can probably guess what np.ones creates.

Related is np.empty, which creates arrays in memory that can later be populated with data

z = np.empty(3)

z

array([0., 0., 0.])

The numbers you see here are garbage values.

(Python allocates 3 contiguous 64 bit pieces of memory, and the existing contents of those memory slots are interpreted as float64 values)

To set up a grid of evenly spaced numbers use np.linspace

z = np.linspace(2, 4, 5) # From 2 to 4, with 5 elements

To create an identity matrix use either np.identity or np.eye

z = np.identity(2)

z

array([[1., 0.],

[0., 1.]])

In addition, NumPy arrays can be created from Python lists, tuples, etc. using np.array

z = np.array([10, 20]) # ndarray from Python list

z

array([10, 20])

type(z)

numpy.ndarray

z = np.array((10, 20), dtype=float) # Here 'float' is equivalent to 'np.float64'

z

array([10., 20.])

z = np.array([[1, 2], [3, 4]]) # 2D array from a list of lists

z

array([[1, 2],

[3, 4]])

See also np.asarray, which performs a similar function, but does not make

a distinct copy of data already in a NumPy array.

To read in the array data from a text file containing numeric data use np.loadtxt —see the documentation for details.

10.2.4. Array Indexing#

For a flat array, indexing is the same as Python sequences:

z = np.linspace(1, 2, 5)

z

array([1. , 1.25, 1.5 , 1.75, 2. ])

z[0]

np.float64(1.0)

z[0:2] # Two elements, starting at element 0

array([1. , 1.25])

z[-1]

np.float64(2.0)

For 2D arrays the index syntax is as follows:

z = np.array([[1, 2], [3, 4]])

z

array([[1, 2],

[3, 4]])

z[0, 0]

np.int64(1)

z[0, 1]

np.int64(2)

And so on.

Columns and rows can be extracted as follows

z[0, :]

array([1, 2])

z[:, 1]

array([2, 4])

NumPy arrays of integers can also be used to extract elements

z = np.linspace(2, 4, 5)

z

array([2. , 2.5, 3. , 3.5, 4. ])

indices = np.array((0, 2, 3))

z[indices]

array([2. , 3. , 3.5])

Finally, an array of dtype bool can be used to extract elements

z

array([2. , 2.5, 3. , 3.5, 4. ])

d = np.array([0, 1, 1, 0, 0], dtype=bool)

d

array([False, True, True, False, False])

z[d]

array([2.5, 3. ])

We’ll see why this is useful below.

An aside: all elements of an array can be set equal to one number using slice notation

z = np.empty(3)

z

array([2. , 3. , 3.5])

z[:] = 42

z

array([42., 42., 42.])

10.2.5. Array Methods#

Arrays have useful methods, all of which are carefully optimized

a = np.array((4, 3, 2, 1))

a

array([4, 3, 2, 1])

a.sort() # Sorts a in place

a

array([1, 2, 3, 4])

a.sum() # Sum

np.int64(10)

a.mean() # Mean

np.float64(2.5)

a.max() # Max

np.int64(4)

a.argmax() # Returns the index of the maximal element

np.int64(3)

a.cumsum() # Cumulative sum of the elements of a

array([ 1, 3, 6, 10])

a.cumprod() # Cumulative product of the elements of a

array([ 1, 2, 6, 24])

a.var() # Variance

np.float64(1.25)

a.std() # Standard deviation

np.float64(1.118033988749895)

a.shape = (2, 2)

a.T # Equivalent to a.transpose()

array([[1, 3],

[2, 4]])

Another method worth knowing is searchsorted().

If z is a nondecreasing array, then z.searchsorted(a) returns the index of

the first element of z that is >= a

z = np.linspace(2, 4, 5)

z

array([2. , 2.5, 3. , 3.5, 4. ])

z.searchsorted(2.2)

np.int64(1)

10.3. Arithmetic Operations#

The operators +, -, *, / and ** all act elementwise on arrays

a = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4])

b = np.array([5, 6, 7, 8])

a + b

array([ 6, 8, 10, 12])

a * b

array([ 5, 12, 21, 32])

We can add a scalar to each element as follows

a + 10

array([11, 12, 13, 14])

Scalar multiplication is similar

a * 10

array([10, 20, 30, 40])

The two-dimensional arrays follow the same general rules

A = np.ones((2, 2))

B = np.ones((2, 2))

A + B

array([[2., 2.],

[2., 2.]])

A + 10

array([[11., 11.],

[11., 11.]])

A * B

array([[1., 1.],

[1., 1.]])

In particular, A * B is not the matrix product, it is an element-wise product.

10.4. Matrix Multiplication#

We use the @ symbol for matrix multiplication, as follows:

A = np.ones((2, 2))

B = np.ones((2, 2))

A @ B

array([[2., 2.],

[2., 2.]])

The syntax works with flat arrays — NumPy makes an educated guess of what you want:

A @ (0, 1)

array([1., 1.])

Since we are post-multiplying, the tuple is treated as a column vector.

10.5. Broadcasting#

(This section extends an excellent discussion of broadcasting provided by Jake VanderPlas.)

Note

Broadcasting is a very important aspect of NumPy. At the same time, advanced broadcasting is relatively complex and some of the details below can be skimmed on first pass.

In element-wise operations, arrays may not have the same shape.

When this happens, NumPy will automatically expand arrays to the same shape whenever possible.

This useful (but sometimes confusing) feature in NumPy is called broadcasting.

The value of broadcasting is that

forloops can be avoided, which helps numerical code run fast andbroadcasting can allow us to implement operations on arrays without actually creating some dimensions of these arrays in memory, which can be important when arrays are large.

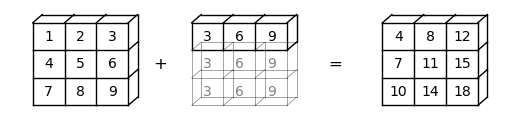

For example, suppose a is a \(3 \times 3\) array (a -> (3, 3)), while b is a flat array with three elements (b -> (3,)).

When adding them together, NumPy will automatically expand b -> (3,) to b -> (3, 3).

The element-wise addition will result in a \(3 \times 3\) array

a = np.array(

[[1, 2, 3],

[4, 5, 6],

[7, 8, 9]])

b = np.array([3, 6, 9])

a + b

array([[ 4, 8, 12],

[ 7, 11, 15],

[10, 14, 18]])

Here is a visual representation of this broadcasting operation:

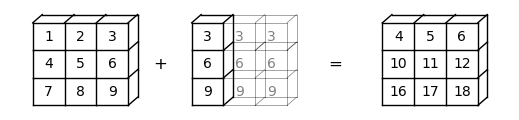

How about b -> (3, 1)?

In this case, NumPy will automatically expand b -> (3, 1) to b -> (3, 3).

Element-wise addition will then result in a \(3 \times 3\) matrix

b.shape = (3, 1)

a + b

array([[ 4, 5, 6],

[10, 11, 12],

[16, 17, 18]])

Here is a visual representation of this broadcasting operation:

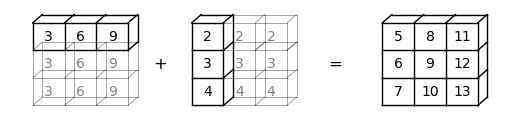

In some cases, both operands will be expanded.

When we have a -> (3,) and b -> (3, 1), a will be expanded to a -> (3, 3), and b will be expanded to b -> (3, 3).

In this case, element-wise addition will result in a \(3 \times 3\) matrix

a = np.array([3, 6, 9])

b = np.array([2, 3, 4])

b.shape = (3, 1)

a + b

array([[ 5, 8, 11],

[ 6, 9, 12],

[ 7, 10, 13]])

Here is a visual representation of this broadcasting operation:

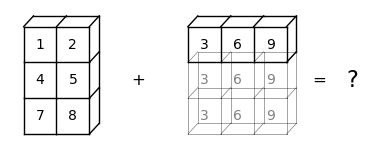

While broadcasting is very useful, it can sometimes seem confusing.

For example, let’s try adding a -> (3, 2) and b -> (3,).

a = np.array(

[[1, 2],

[4, 5],

[7, 8]])

b = np.array([3, 6, 9])

a + b

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[62], line 7

1 a = np.array(

2 [[1, 2],

3 [4, 5],

4 [7, 8]])

5 b = np.array([3, 6, 9])

----> 7 a + b

ValueError: operands could not be broadcast together with shapes (3,2) (3,)

The ValueError tells us that operands could not be broadcast together.

Here is a visual representation to show why this broadcasting cannot be executed:

We can see that NumPy cannot expand the arrays to the same size.

It is because, when b is expanded from b -> (3,) to b -> (3, 3), NumPy cannot match b with a -> (3, 2).

Things get even trickier when we move to higher dimensions.

To help us, we can use the following list of rules:

Step 1: When the dimensions of two arrays do not match, NumPy will expand the one with fewer dimensions by adding dimension(s) on the left of the existing dimensions.

For example, if

a -> (3, 3)andb -> (3,), then broadcasting will add a dimension to the left so thatb -> (1, 3);If

a -> (2, 2, 2)andb -> (2, 2), then broadcasting will add a dimension to the left so thatb -> (1, 2, 2);If

a -> (3, 2, 2)andb -> (2,), then broadcasting will add two dimensions to the left so thatb -> (1, 1, 2)(you can also see this process as going through Step 1 twice).

Step 2: When the two arrays have the same dimension but different shapes, NumPy will try to expand dimensions where the shape index is 1.

For example, if

a -> (1, 3)andb -> (3, 1), then broadcasting will expand dimensions with shape 1 in bothaandbso thata -> (3, 3)andb -> (3, 3);If

a -> (2, 2, 2)andb -> (1, 2, 2), then broadcasting will expand the first dimension ofbso thatb -> (2, 2, 2);If

a -> (3, 2, 2)andb -> (1, 1, 2), then broadcasting will expandbon all dimensions with shape 1 so thatb -> (3, 2, 2).

Step 3: After Step 1 and 2, if the two arrays still do not match, a

ValueErrorwill be raised. For example, supposea -> (2, 2, 3)andb -> (2, 2)By Step 1,

bwill be expanded tob -> (1, 2, 2);By Step 2,

bwill be expanded tob -> (2, 2, 2);We can see that they do not match each other after the first two steps. Thus, a

ValueErrorwill be raised

10.6. Mutability and Copying Arrays#

NumPy arrays are mutable data types, like Python lists.

In other words, their contents can be altered (mutated) in memory after initialization.

This is convenient but, when combined with Python’s naming and reference model, can lead to mistakes by NumPy beginners.

In this section we review some key issues.

10.6.1. Mutability#

We already saw examples of multability above.

Here’s another example of mutation of a NumPy array

a = np.array([42, 44])

a

array([42, 44])

a[-1] = 0 # Change last element to 0

a

array([42, 0])

Mutability leads to the following behavior (which can be shocking to MATLAB programmers…)

a = np.random.randn(3)

a

array([0.16029118, 0.37687491, 1.1726372 ])

b = a

b[0] = 0.0

a

array([0. , 0.37687491, 1.1726372 ])

What’s happened is that we have changed a by changing b.

The name b is bound to a and becomes just another reference to the

array (the Python assignment model is described in more detail later in the course).

Hence, it has equal rights to make changes to that array.

This is in fact the most sensible default behavior!

It means that we pass around only pointers to data, rather than making copies.

Making copies is expensive in terms of both speed and memory.

10.6.2. Making Copies#

It is of course possible to make b an independent copy of a when required.

This can be done using np.copy

a = np.random.randn(3)

a

array([-1.09723088, 0.20076804, 0.87300441])

b = np.copy(a)

b

array([-1.09723088, 0.20076804, 0.87300441])

Now b is an independent copy (called a deep copy)

b[:] = 1

b

array([1., 1., 1.])

a

array([-1.09723088, 0.20076804, 0.87300441])

Note that the change to b has not affected a.

10.7. Additional Features#

Let’s look at some other useful features of NumPy.

10.7.1. Universal Functions#

NumPy provides versions of the standard functions log, exp, sin, etc. that act element-wise on arrays

z = np.array([1, 2, 3])

np.sin(z)

array([0.84147098, 0.90929743, 0.14112001])

This eliminates the need for explicit element-by-element loops such as

n = len(z)

y = np.empty(n)

for i in range(n):

y[i] = np.sin(z[i])

Because they act element-wise on arrays, these functions are sometimes called vectorized functions.

In NumPy-speak, they are also called ufuncs, or universal functions.

As we saw above, the usual arithmetic operations (+, *, etc.) also

work element-wise, and combining these with the ufuncs gives a very large set of fast element-wise functions.

z

array([1, 2, 3])

(1 / np.sqrt(2 * np.pi)) * np.exp(- 0.5 * z**2)

array([0.24197072, 0.05399097, 0.00443185])

Not all user-defined functions will act element-wise.

For example, passing the function f defined below a NumPy array causes a ValueError

def f(x):

return 1 if x > 0 else 0

The NumPy function np.where provides a vectorized alternative:

x = np.random.randn(4)

x

array([ 0.18885998, -0.26484546, -1.09583508, -1.03728248])

np.where(x > 0, 1, 0) # Insert 1 if x > 0 true, otherwise 0

array([1, 0, 0, 0])

You can also use np.vectorize to vectorize a given function

f = np.vectorize(f)

f(x) # Passing the same vector x as in the previous example

array([1, 0, 0, 0])

However, this approach doesn’t always obtain the same speed as a more carefully crafted vectorized function.

(Later we’ll see that JAX has a powerful version of np.vectorize that can and usually does generate highly efficient code.)

10.7.2. Comparisons#

As a rule, comparisons on arrays are done element-wise

z = np.array([2, 3])

y = np.array([2, 3])

z == y

array([ True, True])

y[0] = 5

z == y

array([False, True])

z != y

array([ True, False])

The situation is similar for >, <, >= and <=.

We can also do comparisons against scalars

z = np.linspace(0, 10, 5)

z

array([ 0. , 2.5, 5. , 7.5, 10. ])

z > 3

array([False, False, True, True, True])

This is particularly useful for conditional extraction

b = z > 3

b

array([False, False, True, True, True])

z[b]

array([ 5. , 7.5, 10. ])

Of course we can—and frequently do—perform this in one step

z[z > 3]

array([ 5. , 7.5, 10. ])

10.7.3. Sub-packages#

NumPy provides some additional functionality related to scientific programming through its sub-packages.

We’ve already seen how we can generate random variables using np.random

z = np.random.randn(10000) # Generate standard normals

y = np.random.binomial(10, 0.5, size=1000) # 1,000 draws from Bin(10, 0.5)

y.mean()

np.float64(5.062)

Another commonly used subpackage is np.linalg

A = np.array([[1, 2], [3, 4]])

np.linalg.det(A) # Compute the determinant

np.float64(-2.0000000000000004)

np.linalg.inv(A) # Compute the inverse

array([[-2. , 1. ],

[ 1.5, -0.5]])

Much of this functionality is also available in SciPy, a collection of modules that are built on top of NumPy.

We’ll cover the SciPy versions in more detail soon.

For a comprehensive list of what’s available in NumPy see this documentation.

10.7.4. Implicit Multithreading#

Previously we discussed the concept of parallelization via multithreading.

NumPy tries to implement multithreading in much of its compiled code.

Let’s look at an example to see this in action.

The next piece of code computes the eigenvalues of a large number of randomly generated matrices.

It takes a few seconds to run.

n = 20

m = 1000

for i in range(n):

X = np.random.randn(m, m)

λ = np.linalg.eigvals(X)

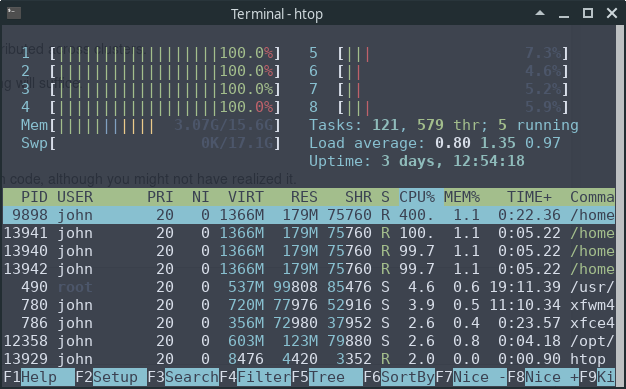

Now, let’s look at the output of the htop system monitor on our machine while this code is running:

We can see that 4 of the 8 CPUs are running at full speed.

This is because NumPy’s eigvals routine neatly splits up the tasks and

distributes them to different threads.

10.8. Exercises#

Exercise 10.1

Consider the polynomial expression

Earlier, you wrote a simple function p(x, coeff) to evaluate (10.1) without considering efficiency.

Now write a new function that does the same job, but uses NumPy arrays and array operations for its computations, rather than any form of Python loop.

(Such functionality is already implemented as np.poly1d, but for the sake of the exercise don’t use this class)

Hint

Use np.cumprod()

Solution

This code does the job

def p(x, coef):

X = np.ones_like(coef)

X[1:] = x

y = np.cumprod(X) # y = [1, x, x**2,...]

return coef @ y

Let’s test it

x = 2

coef = np.linspace(2, 4, 3)

print(coef)

print(p(x, coef))

# For comparison

q = np.poly1d(np.flip(coef))

print(q(x))

[2. 3. 4.]

24.0

24.0

Exercise 10.2

Let q be a NumPy array of length n with q.sum() == 1.

Suppose that q represents a probability mass function.

We wish to generate a discrete random variable \(x\) such that \(\mathbb P\{x = i\} = q_i\).

In other words, x takes values in range(len(q)) and x = i with probability q[i].

The standard (inverse transform) algorithm is as follows:

Divide the unit interval \([0, 1]\) into \(n\) subintervals \(I_0, I_1, \ldots, I_{n-1}\) such that the length of \(I_i\) is \(q_i\).

Draw a uniform random variable \(U\) on \([0, 1]\) and return the \(i\) such that \(U \in I_i\).

The probability of drawing \(i\) is the length of \(I_i\), which is equal to \(q_i\).

We can implement the algorithm as follows

from random import uniform

def sample(q):

a = 0.0

U = uniform(0, 1)

for i in range(len(q)):

if a < U <= a + q[i]:

return i

a = a + q[i]

If you can’t see how this works, try thinking through the flow for a simple example, such as q = [0.25, 0.75]

It helps to sketch the intervals on paper.

Your exercise is to speed it up using NumPy, avoiding explicit loops

Hint

Use np.searchsorted and np.cumsum

If you can, implement the functionality as a class called DiscreteRV, where

the data for an instance of the class is the vector of probabilities

qthe class has a

draw()method, which returns one draw according to the algorithm described above

If you can, write the method so that draw(k) returns k draws from q.

Solution

Here’s our first pass at a solution:

from numpy import cumsum

from numpy.random import uniform

class DiscreteRV:

"""

Generates an array of draws from a discrete random variable with vector of

probabilities given by q.

"""

def __init__(self, q):

"""

The argument q is a NumPy array, or array like, nonnegative and sums

to 1

"""

self.q = q

self.Q = cumsum(q)

def draw(self, k=1):

"""

Returns k draws from q. For each such draw, the value i is returned

with probability q[i].

"""

return self.Q.searchsorted(uniform(0, 1, size=k))

The logic is not obvious, but if you take your time and read it slowly, you will understand.

There is a problem here, however.

Suppose that q is altered after an instance of discreteRV is

created, for example by

q = (0.1, 0.9)

d = DiscreteRV(q)

d.q = (0.5, 0.5)

The problem is that Q does not change accordingly, and Q is the

data used in the draw method.

To deal with this, one option is to compute Q every time the draw

method is called.

But this is inefficient relative to computing Q once-off.

A better option is to use descriptors.

A solution from the quantecon library using descriptors that behaves as we desire can be found here.

Exercise 10.3

Recall our earlier discussion of the empirical cumulative distribution function.

Your task is to

Make the

__call__method more efficient using NumPy.Add a method that plots the ECDF over \([a, b]\), where \(a\) and \(b\) are method parameters.

Solution

An example solution is given below.

In essence, we’ve just taken this code from QuantEcon and added in a plot method

"""

Modifies ecdf.py from QuantEcon to add in a plot method

"""

class ECDF:

"""

One-dimensional empirical distribution function given a vector of

observations.

Parameters

----------

observations : array_like

An array of observations

Attributes

----------

observations : array_like

An array of observations

"""

def __init__(self, observations):

self.observations = np.asarray(observations)

def __call__(self, x):

"""

Evaluates the ecdf at x

Parameters

----------

x : scalar(float)

The x at which the ecdf is evaluated

Returns

-------

scalar(float)

Fraction of the sample less than x

"""

return np.mean(self.observations <= x)

def plot(self, ax, a=None, b=None):

"""

Plot the ecdf on the interval [a, b].

Parameters

----------

a : scalar(float), optional(default=None)

Lower endpoint of the plot interval

b : scalar(float), optional(default=None)

Upper endpoint of the plot interval

"""

# === choose reasonable interval if [a, b] not specified === #

if a is None:

a = self.observations.min() - self.observations.std()

if b is None:

b = self.observations.max() + self.observations.std()

# === generate plot === #

x_vals = np.linspace(a, b, num=100)

f = np.vectorize(self.__call__)

ax.plot(x_vals, f(x_vals))

plt.show()

Here’s an example of usage

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

X = np.random.randn(1000)

F = ECDF(X)

F.plot(ax)

Exercise 10.4

Recall that broadcasting in Numpy can help us conduct element-wise operations on arrays with different number of dimensions without using for loops.

In this exercise, try to use for loops to replicate the result of the following broadcasting operations.

Part1: Try to replicate this simple example using for loops and compare your results with the broadcasting operation below.

np.random.seed(123)

x = np.random.randn(4, 4)

y = np.random.randn(4)

A = x / y

Here is the output

print(A)

Part2: Move on to replicate the result of the following broadcasting operation. Meanwhile, compare the speeds of broadcasting and the for loop you implement.

For this part of the exercise you can use the tic/toc functions from the quantecon library to time the execution.

Let’s make sure this library is installed.

!pip install quantecon

Now we can import the quantecon package.

np.random.seed(123)

x = np.random.randn(1000, 100, 100)

y = np.random.randn(100)

with qe.Timer("Broadcasting operation"):

B = x / y

Broadcasting operation: 0.0282 seconds elapsed

Here is the output

print(B)

Solution

Part 1 Solution

np.random.seed(123)

x = np.random.randn(4, 4)

y = np.random.randn(4)

C = np.empty_like(x)

n = len(x)

for i in range(n):

for j in range(n):

C[i, j] = x[i, j] / y[j]

Compare the results to check your answer

print(C)

You can also use array_equal() to check your answer

print(np.array_equal(A, C))

True

Part 2 Solution

np.random.seed(123)

x = np.random.randn(1000, 100, 100)

y = np.random.randn(100)

with qe.Timer("For loop operation"):

D = np.empty_like(x)

d1, d2, d3 = x.shape

for i in range(d1):

for j in range(d2):

for k in range(d3):

D[i, j, k] = x[i, j, k] / y[k]

For loop operation: 5.9003 seconds elapsed

Note that the for loop takes much longer than the broadcasting operation.

Compare the results to check your answer

print(D)

print(np.array_equal(B, D))

True