13. Numba#

In addition to what’s in Anaconda, this lecture will need the following libraries:

!pip install quantecon

Please also make sure that you have the latest version of Anaconda, since old versions are a common source of errors.

Let’s start with some imports:

import numpy as np

import quantecon as qe

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

13.1. Overview#

In an earlier lecture we learned about vectorization, which is one method to improve speed and efficiency in numerical work.

Vectorization involves sending array processing operations in batch to efficient low-level code.

However, as discussed previously, vectorization has several weaknesses.

One is that it is highly memory-intensive when working with large amounts of data.

Another is that the set of algorithms that can be entirely vectorized is not universal.

In fact, for some algorithms, vectorization is ineffective.

Fortunately, a new Python library called Numba solves many of these problems.

It does so through something called just in time (JIT) compilation.

The key idea is to compile functions to native machine code instructions on the fly.

When it succeeds, the compiled code is extremely fast.

Beyond speed gains from compilation, Numba is specifically designed for numerical work and can also do other tricks such as Multithreaded Loops in Numba.

This lecture introduces the main ideas.

13.2. Compiling Functions#

As stated above, Numba’s primary use is compiling functions to fast native machine code during runtime.

13.2.1. An Example#

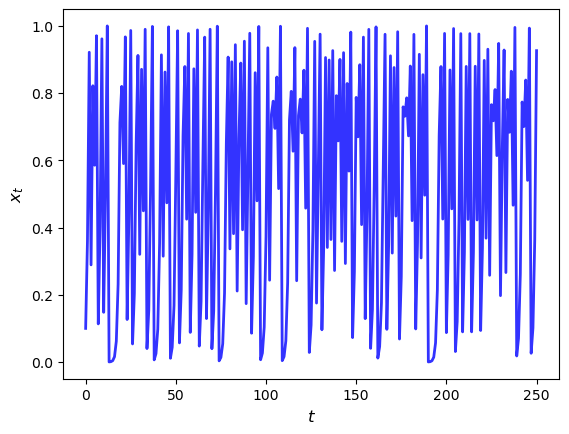

Let’s consider a problem that is difficult to vectorize: generating the trajectory of a difference equation given an initial condition.

We will take the difference equation to be the quadratic map

In what follows we set

α = 4.0

Here’s the plot of a typical trajectory, starting from \(x_0 = 0.1\), with \(t\) on the x-axis

def qm(x0, n):

x = np.empty(n+1)

x[0] = x0

for t in range(n):

x[t+1] = α * x[t] * (1 - x[t])

return x

x = qm(0.1, 250)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(x, 'b-', lw=2, alpha=0.8)

ax.set_xlabel('$t$', fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel('$x_{t}$', fontsize = 12)

plt.show()

To speed the function qm up using Numba, our first step is

from numba import jit

qm_numba = jit(qm)

The function qm_numba is a version of qm that is “targeted” for

JIT-compilation.

We will explain what this means momentarily.

Let’s time and compare identical function calls across these two versions, starting with the original function qm:

n = 10_000_000

with qe.Timer() as timer1:

qm(0.1, int(n))

time1 = timer1.elapsed

4.5272 seconds elapsed

Now let’s try qm_numba

with qe.Timer() as timer2:

qm_numba(0.1, int(n))

time2 = timer2.elapsed

0.2180 seconds elapsed

This is already a very large speed gain.

In fact, the next time and all subsequent times it runs even faster as the function has been compiled and is in memory:

with qe.Timer() as timer3:

qm_numba(0.1, int(n))

time3 = timer3.elapsed

0.0701 seconds elapsed

time1 / time3 # Calculate speed gain

64.53685577171446

This kind of speed gain is impressive relative to how simple and clear the modification is.

13.2.2. How and When it Works#

Numba attempts to generate fast machine code using the infrastructure provided by the LLVM Project.

It does this by inferring type information on the fly.

(See our earlier lecture on scientific computing for a discussion of types.)

The basic idea is this:

Python is very flexible and hence we could call the function qm with many types.

e.g.,

x0could be a NumPy array or a list,ncould be an integer or a float, etc.

This makes it hard to pre-compile the function (i.e., compile before runtime).

However, when we do actually call the function, say by running

qm(0.5, 10), the types ofx0andnbecome clear.Moreover, the types of other variables in

qmcan be inferred once the input types are known.So the strategy of Numba and other JIT compilers is to wait until this moment, and then compile the function.

That’s why it is called “just-in-time” compilation.

Note that, if you make the call qm(0.5, 10) and then follow it with qm(0.9, 20), compilation only takes place on the first call.

The compiled code is then cached and recycled as required.

This is why, in the code above, time3 is smaller than time2.

13.3. Decorator Notation#

In the code above we created a JIT compiled version of qm via the call

qm_numba = jit(qm)

In practice this would typically be done using an alternative decorator syntax.

(We discuss decorators in a separate lecture but you can skip the details at this stage.)

Let’s see how this is done.

To target a function for JIT compilation we can put @jit before the function definition.

Here’s what this looks like for qm

@jit

def qm(x0, n):

x = np.empty(n+1)

x[0] = x0

for t in range(n):

x[t+1] = α * x[t] * (1 - x[t])

return x

This is equivalent to adding qm = jit(qm) after the function definition.

The following now uses the jitted version:

with qe.Timer(precision=4):

qm(0.1, 100_000)

0.0752 seconds elapsed

with qe.Timer(precision=4):

qm(0.1, 100_000)

0.0003 seconds elapsed

Numba also provides several arguments for decorators to accelerate computation and cache functions – see here.

13.4. Type Inference#

Successful type inference is a key part of JIT compilation.

As you can imagine, inferring types is easier for simple Python objects (e.g., simple scalar data types such as floats and integers).

Numba also plays well with NumPy arrays, which have well-defined types.

In an ideal setting, Numba can infer all necessary type information.

This allows it to generate native machine code, without having to call the Python runtime environment.

In such a setting, Numba will be on par with machine code from low-level languages.

When Numba cannot infer all type information, it will raise an error.

For example, in the (artificial) setting below, Numba is unable to determine the type of function mean when compiling the function bootstrap

@jit

def bootstrap(data, statistics, n):

bootstrap_stat = np.empty(n)

n = len(data)

for i in range(n_resamples):

resample = np.random.choice(data, size=n, replace=True)

bootstrap_stat[i] = statistics(resample)

return bootstrap_stat

# No decorator here.

def mean(data):

return np.mean(data)

data = np.array((2.3, 3.1, 4.3, 5.9, 2.1, 3.8, 2.2))

n_resamples = 10

# This code throws an error

try:

bootstrap(data, mean, n_resamples)

except Exception as e:

print(e)

Failed in nopython mode pipeline (step: nopython frontend)

non-precise type pyobject

During: typing of argument at /tmp/ipykernel_2340/3796191009.py (1)

File "../../../../../../tmp/ipykernel_2340/3796191009.py", line 1:

<source missing, REPL/exec in use?>

During: Pass nopython_type_inference

This error may have been caused by the following argument(s):

- argument 1: Cannot determine Numba type of <class 'function'>

We can fix this error easily in this case by compiling mean.

@jit

def mean(data):

return np.mean(data)

with qe.Timer():

bootstrap(data, mean, n_resamples)

0.2622 seconds elapsed

13.5. Compiling Classes#

As mentioned above, at present Numba can only compile a subset of Python.

However, that subset is ever expanding.

Notably, Numba is now quite effective at compiling classes.

If a class is successfully compiled, then its methods act as JIT-compiled functions.

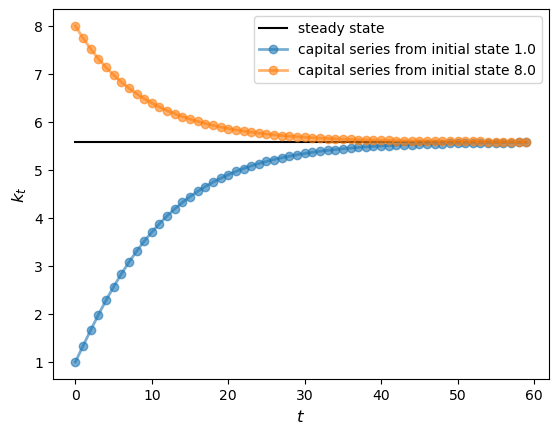

To give one example, let’s consider the class for analyzing the Solow growth model we created in this lecture.

To compile this class we use the @jitclass decorator:

from numba import float64

from numba.experimental import jitclass

Notice that we also imported something called float64.

This is a data type representing standard floating point numbers.

We are importing it here because Numba needs a bit of extra help with types when it tries to deal with classes.

Here’s our code:

solow_data = [

('n', float64),

('s', float64),

('δ', float64),

('α', float64),

('z', float64),

('k', float64)

]

@jitclass(solow_data)

class Solow:

r"""

Implements the Solow growth model with the update rule

k_{t+1} = [(s z k^α_t) + (1 - δ)k_t] /(1 + n)

"""

def __init__(self, n=0.05, # population growth rate

s=0.25, # savings rate

δ=0.1, # depreciation rate

α=0.3, # share of labor

z=2.0, # productivity

k=1.0): # current capital stock

self.n, self.s, self.δ, self.α, self.z = n, s, δ, α, z

self.k = k

def h(self):

"Evaluate the h function"

# Unpack parameters (get rid of self to simplify notation)

n, s, δ, α, z = self.n, self.s, self.δ, self.α, self.z

# Apply the update rule

return (s * z * self.k**α + (1 - δ) * self.k) / (1 + n)

def update(self):

"Update the current state (i.e., the capital stock)."

self.k = self.h()

def steady_state(self):

"Compute the steady state value of capital."

# Unpack parameters (get rid of self to simplify notation)

n, s, δ, α, z = self.n, self.s, self.δ, self.α, self.z

# Compute and return steady state

return ((s * z) / (n + δ))**(1 / (1 - α))

def generate_sequence(self, t):

"Generate and return a time series of length t"

path = []

for i in range(t):

path.append(self.k)

self.update()

return path

First we specified the types of the instance data for the class in

solow_data.

After that, targeting the class for JIT compilation only requires adding

@jitclass(solow_data) before the class definition.

When we call the methods in the class, the methods are compiled just like functions.

s1 = Solow()

s2 = Solow(k=8.0)

T = 60

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

# Plot the common steady state value of capital

ax.plot([s1.steady_state()]*T, 'k-', label='steady state')

# Plot time series for each economy

for s in s1, s2:

lb = f'capital series from initial state {s.k}'

ax.plot(s.generate_sequence(T), 'o-', lw=2, alpha=0.6, label=lb)

ax.set_ylabel('$k_{t}$', fontsize=12)

ax.set_xlabel('$t$', fontsize=12)

ax.legend()

plt.show()

13.6. Dangers and Limitations#

Let’s review the above and add some cautionary notes.

13.6.1. Limitations#

As we’ve seen, Numba needs to infer type information on all variables to generate fast machine-level instructions.

For simple routines, Numba infers types very well.

For larger ones, or for routines using external libraries, it can easily fail.

Hence, it’s prudent when using Numba to focus on speeding up small, time-critical snippets of code.

This will give you much better performance than blanketing your Python programs with @njit statements.

13.6.2. A Gotcha: Global Variables#

Here’s another thing to be careful about when using Numba.

Consider the following example

a = 1

@jit

def add_a(x):

return a + x

print(add_a(10))

11

a = 2

print(add_a(10))

11

Notice that changing the global had no effect on the value returned by the function.

When Numba compiles machine code for functions, it treats global variables as constants to ensure type stability.

13.7. Multithreaded Loops in Numba#

In addition to JIT compilation, Numba provides powerful support for parallel computing on CPUs.

By distributing computations across multiple CPU cores, we can achieve significant speed gains for many numerical algorithms.

The key tool for parallelization in Numba is the prange function, which tells Numba to execute loop iterations in parallel across available CPU cores.

This approach to multithreading works well for a wide range of problems in scientific computing and quantitative economics.

To illustrate, let’s look first at a simple, single-threaded (i.e., non-parallelized) piece of code.

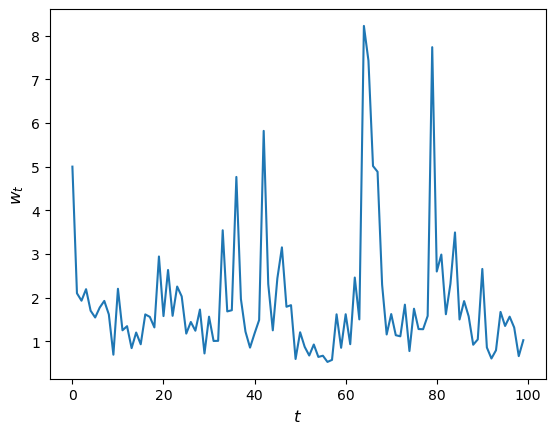

The code simulates updating the wealth \(w_t\) of a household via the rule

Here

\(R\) is the gross rate of return on assets

\(s\) is the savings rate of the household and

\(y\) is labor income.

We model both \(R\) and \(y\) as independent draws from a lognormal distribution.

Here’s the code:

from numpy.random import randn

from numba import njit

@njit

def h(w, r=0.1, s=0.3, v1=0.1, v2=1.0):

"""

Updates household wealth.

"""

# Draw shocks

R = np.exp(v1 * randn()) * (1 + r)

y = np.exp(v2 * randn())

# Update wealth

w = R * s * w + y

return w

Let’s have a look at how wealth evolves under this rule.

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

T = 100

w = np.empty(T)

w[0] = 5

for t in range(T-1):

w[t+1] = h(w[t])

ax.plot(w)

ax.set_xlabel('$t$', fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel('$w_{t}$', fontsize=12)

plt.show()

Now let’s suppose that we have a large population of households and we want to know what median wealth will be.

This is not easy to solve with pencil and paper, so we will use simulation instead.

In particular, we will simulate a large number of households and then calculate median wealth for this group.

Suppose we are interested in the long-run average of this median over time.

It turns out that, for the specification that we’ve chosen above, we can calculate this by taking a one-period snapshot of what has happened to median wealth of the group at the end of a long simulation.

Moreover, provided the simulation period is long enough, initial conditions don’t matter.

This is due to something called ergodicity, which we will discuss later on.

So, in summary, we are going to simulate 50,000 households by

arbitrarily setting initial wealth to 1 and

simulating forward in time for 1,000 periods.

Then we’ll calculate median wealth at the end period.

Here’s the code:

@njit

def compute_long_run_median(w0=1, T=1000, num_reps=50_000):

obs = np.empty(num_reps)

for i in range(num_reps):

w = w0

for t in range(T):

w = h(w)

obs[i] = w

return np.median(obs)

Let’s see how fast this runs:

with qe.Timer():

compute_long_run_median()

6.7290 seconds elapsed

To speed this up, we’re going to parallelize it via multithreading.

To do so, we add the parallel=True flag and change range to prange:

from numba import prange

@njit(parallel=True)

def compute_long_run_median_parallel(w0=1, T=1000, num_reps=50_000):

obs = np.empty(num_reps)

for i in prange(num_reps):

w = w0

for t in range(T):

w = h(w)

obs[i] = w

return np.median(obs)

Let’s look at the timing:

with qe.Timer():

compute_long_run_median_parallel()

0.9911 seconds elapsed

The speed-up is significant.

13.8. Exercises#

Exercise 13.1

Previously we considered how to approximate \(\pi\) by Monte Carlo.

Use the same idea here, but make the code efficient using Numba.

Compare speed with and without Numba when the sample size is large.

Solution

Here is one solution:

from random import uniform

@jit

def calculate_pi(n=1_000_000):

count = 0

for i in range(n):

u, v = uniform(0, 1), uniform(0, 1)

d = np.sqrt((u - 0.5)**2 + (v - 0.5)**2)

if d < 0.5:

count += 1

area_estimate = count / n

return area_estimate * 4 # dividing by radius**2

Now let’s see how fast it runs:

with qe.Timer():

calculate_pi()

0.1866 seconds elapsed

with qe.Timer():

calculate_pi()

0.0325 seconds elapsed

If we switch off JIT compilation by removing @njit, the code takes around

150 times as long on our machine.

So we get a speed gain of 2 orders of magnitude–which is huge–by adding four characters.

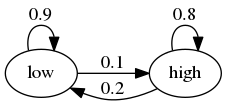

Exercise 13.2

In the Introduction to Quantitative Economics with Python lecture series you can learn all about finite-state Markov chains.

For now, let’s just concentrate on simulating a very simple example of such a chain.

Suppose that the volatility of returns on an asset can be in one of two regimes — high or low.

The transition probabilities across states are as follows

For example, let the period length be one day, and suppose the current state is high.

We see from the graph that the state tomorrow will be

high with probability 0.8

low with probability 0.2

Your task is to simulate a sequence of daily volatility states according to this rule.

Set the length of the sequence to n = 1_000_000 and start in the high state.

Implement a pure Python version and a Numba version, and compare speeds.

To test your code, evaluate the fraction of time that the chain spends in the low state.

If your code is correct, it should be about 2/3.

Hint

Represent the low state as 0 and the high state as 1.

If you want to store integers in a NumPy array and then apply JIT compilation, use

x = np.empty(n, dtype=np.int_).

Solution

We let

0 represent “low”

1 represent “high”

p, q = 0.1, 0.2 # Prob of leaving low and high state respectively

Here’s a pure Python version of the function

def compute_series(n):

x = np.empty(n, dtype=np.int_)

x[0] = 1 # Start in state 1

U = np.random.uniform(0, 1, size=n)

for t in range(1, n):

current_x = x[t-1]

if current_x == 0:

x[t] = U[t] < p

else:

x[t] = U[t] > q

return x

Let’s run this code and check that the fraction of time spent in the low state is about 0.666

n = 1_000_000

x = compute_series(n)

print(np.mean(x == 0)) # Fraction of time x is in state 0

0.66809

This is (approximately) the right output.

Now let’s time it:

with qe.Timer():

compute_series(n)

0.5878 seconds elapsed

Next let’s implement a Numba version, which is easy

compute_series_numba = jit(compute_series)

Let’s check we still get the right numbers

x = compute_series_numba(n)

print(np.mean(x == 0))

0.664802

Let’s see the time

with qe.Timer():

compute_series_numba(n)

0.0213 seconds elapsed

This is a nice speed improvement for one line of code!

Exercise 13.3

In an earlier exercise, we used Numba to accelerate an effort to compute the constant \(\pi\) by Monte Carlo.

Now try adding parallelization and see if you get further speed gains.

You should not expect huge gains here because, while there are many independent tasks (draw point and test if in circle), each one has low execution time.

Generally speaking, parallelization is less effective when the individual tasks to be parallelized are very small relative to total execution time.

This is due to overheads associated with spreading all of these small tasks across multiple CPUs.

Nevertheless, with suitable hardware, it is possible to get nontrivial speed gains in this exercise.

For the size of the Monte Carlo simulation, use something substantial, such as

n = 100_000_000.

Solution

Here is one solution:

from random import uniform

@njit(parallel=True)

def calculate_pi(n=1_000_000):

count = 0

for i in prange(n):

u, v = uniform(0, 1), uniform(0, 1)

d = np.sqrt((u - 0.5)**2 + (v - 0.5)**2)

if d < 0.5:

count += 1

area_estimate = count / n

return area_estimate * 4 # dividing by radius**2

Now let’s see how fast it runs:

with qe.Timer():

calculate_pi()

0.4607 seconds elapsed

with qe.Timer():

calculate_pi()

0.0047 seconds elapsed

By switching parallelization on and off (selecting True or

False in the @njit annotation), we can test the speed gain that

multithreading provides on top of JIT compilation.

On our workstation, we find that parallelization increases execution speed by a factor of 2 or 3.

(If you are executing locally, you will get different numbers, depending mainly on the number of CPUs on your machine.)

Exercise 13.4

In our lecture on SciPy, we discussed pricing a call option in a setting where the underlying stock price had a simple and well-known distribution.

Here we discuss a more realistic setting.

We recall that the price of the option obeys

where

\(\beta\) is a discount factor,

\(n\) is the expiry date,

\(K\) is the strike price and

\(\{S_t\}\) is the price of the underlying asset at each time \(t\).

Suppose that n, β, K = 20, 0.99, 100.

Assume that the stock price obeys

where

Here \(\{\xi_t\}\) and \(\{\eta_t\}\) are IID and standard normal.

(This is a stochastic volatility model, where the volatility \(\sigma_t\) varies over time.)

Use the defaults μ, ρ, ν, S0, h0 = 0.0001, 0.1, 0.001, 10, 0.

(Here S0 is \(S_0\) and h0 is \(h_0\).)

By generating \(M\) paths \(s_0, \ldots, s_n\), compute the Monte Carlo estimate

of the price, applying Numba and parallelization.

Solution

With \(s_t := \ln S_t\), the price dynamics become

Using this fact, the solution can be written as follows.

from numpy.random import randn

M = 10_000_000

n, β, K = 20, 0.99, 100

μ, ρ, ν, S0, h0 = 0.0001, 0.1, 0.001, 10, 0

@njit(parallel=True)

def compute_call_price_parallel(β=β,

μ=μ,

S0=S0,

h0=h0,

K=K,

n=n,

ρ=ρ,

ν=ν,

M=M):

current_sum = 0.0

# For each sample path

for m in prange(M):

s = np.log(S0)

h = h0

# Simulate forward in time

for t in range(n):

s = s + μ + np.exp(h) * randn()

h = ρ * h + ν * randn()

# And add the value max{S_n - K, 0} to current_sum

current_sum += np.maximum(np.exp(s) - K, 0)

return β**n * current_sum / M

Try swapping between parallel=True and parallel=False and noting the run time.

If you are on a machine with many CPUs, the difference should be significant.